Anton Bruckner has never resonated with me the way Mahler has. I don’t seek out his symphonies with any particular enthusiasm. When the mood strikes, I’ll put on a recording and settle into my listening chair, letting the music unfold. Friends speak of transcendence; I’m still trying to find my way in. Yet even if Bruckner has not quite claimed me, my relationship with him has been shaped less by the scores themselves than by the circumstances in which I’ve encountered them. In the few times I’ve heard Bruckner in concert—only three over many years—each performance has stayed with me for reasons that extend beyond the music.

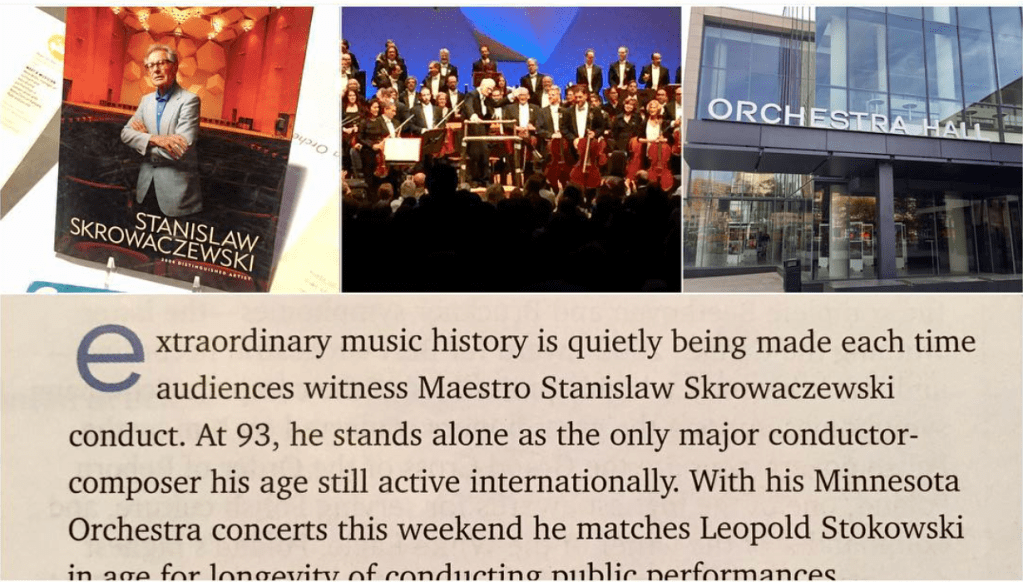

The first was Kurt Masur’s Seattle Symphony account of the Fourth Symphony, which arrived during a crisis moment for the orchestra, with musicians and administration locked in a bitter contract negotiation. Masur’s presence steadied the ensemble, drawing out playing of real warmth and authority; the performance felt like an act of institutional reassurance as much as musical interpretation. A few years later in Minneapolis, I attended what turned out to be Stanislav Skrowaczewski’s final public concert: a compelling reading of the Eighth that ranks among the most engaging concert experiences I’ve had. The lobby that evening was bittersweet—staff were selling off overstock of Skrowaczewski’s recordings. His iconic Vox albums and copies of his celebrated Bruckner Ninth with Minnesota spread across tables while staff shared anecdotes of the man they knew as “Stan.” I’ve wondered since whether he knew it would be his last appearance.

Against that backdrop, my most recent Bruckner encounter carried a different kind of significance. The Berlin Philharmonic brought the Fifth Symphony to Chicago as part of their U.S. tour, and the atmosphere of the night was driven as much by the presence of the Berliners as by the score itself. This was a case where the orchestra’s superlative playing elevated music that doesn’t fully connect with me. I’ve now heard the Berlin Philharmonic twice at Orchestra Hall; both times their sheer quality has made me want to hear them in Berlin.

All of this framed my expectations for Esa-Pekka Salonen’s return to Chicago and my fourth Bruckner performance. Salonen is a conductor I make a point of hearing whenever possible. Last season’s residency was memorable, I caught Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra and came away impressed. His return this season, built around another two-week residency, opened with Bruckner’s Fourth paired with Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto, a program that invited comparison with the earlier Bruckner performances that have lingered in my memory.

Salonen didn’t indulge in mysticism with Bruckner. Instead, his approach emphasized clarity, structure, and swiftness over atmospheric haze. The symphony gained precision and rhythmic drive that made its expansive form easier to follow, even if the spiritual dimension remained elusive. The reading was meticulously crafted: the horn calls in the first movement carried genuine pastoral feeling and the tremolo passages had shimmer and purpose. Salonen and the Chicago Symphony brought out details that often get lost in the texture, giving the piece an orderly profile.

Still, by the finale’s conclusion—some sixty minutes later—I wasn’t any more moved than when we began. This wasn’t the fault of Salonen or the orchestra; the issue, for me, lies in the symphony itself. It remains a work of episodes: some thrilling, others dutiful and static. Salonen’s clear-sighted reading illuminated the score beautifully, but illumination is not the same as transformation, and in this case, it did not transform my relationship to Bruckner. I just couldn’t reach the transcendent place Brucknerians describe.

Information and tickets for Esa-Pekka Salonen’s concerts next week.

Discover more from Gathering Note

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.