Now in its sixth year, Music on the Strait has become a cherished event for music enthusiasts on the Olympic Peninsula. This hidden gem of a music festival may not receive as much attention as some of its counterparts, but it certainly deserves recognition for the incredible performances it brings to this part of the Pacific Northwest year after year.

Continue reading Music on the Strait returns for 6th seasonSeattle Opera’s Rheingold a triumph, with strong cast and ingenious staging

Review published on Seen and Heard International

Not long ago, staging Das Rheingold at the Seattle Opera usually meant that the other three operas in Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle would soon follow. The company was once a Wagnerian destination in the U.S., though not on the same level as the renowned Bayreuth. For decades, when the lights dimmed and the famous chord of E-flat major emerged from the orchestra, slowly at first and then transforming into the flowing Rhine, Seattle audiences and visitors from around the world settled in for a cycle-full of leitmotifs.

That was then. Seattle audiences have not seen Rheingold in ten years. This concise story of power, hubris and consequence is a fanciful two-and-a-half hours of gods and giants; castles and contracts; and of course a subterranean bad guy with an ax to grind. Rheingold sets the whole Ring Cycle in motion, its story serving as the seed of the original sin growing through Wagner’s ambitious four-part drama. But even staged alone – as it was here – there is much to enjoy in this tale of mythic gods with human failings.

Continue reading Seattle Opera’s Rheingold a triumph, with strong cast and ingenious stagingA Revelation of Mahler: Vänskä’s Interpretation Shines in ‘Resurrection’ Symphony

Review published at Seen and Heard International

Mahler performances run the gamut interpretatively. Leonard Bernstein famously pushed an approach that was cosmic in scale, yet also probed the human condition. Rafael Kubelik’s approach was rustic and humane. He grounded his performances in Mahler’s abundant references to nature. There are also the modernists interpretations: Conductors who see Mahler the same way they might think of Schoenberg or Webern — as harbingers of music’s new path in the 20th century. Boulez fits this category well.

Continue reading A Revelation of Mahler: Vänskä’s Interpretation Shines in ‘Resurrection’ SymphonySeattle Symphony’s season penultimate program celebrates Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet

Review published on Seen and Heard International

The Seattle Symphony’s penultimate program of the 2022-23 season embraced the notion of music as a medium for artistic expression – with Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet” at the center. This timeless tale has inspired many a composer, and guest conductor Marin Alsop led the orchestra in three of the most iconic interpretations of the star-crossed lovers and their sword-crossed clans. For the first half of the program, Alsop drew from the oeuvre of Tchaikovsky and her mentor Leonard Bernstein. But the zenith of artistic expression and enjoyment was doubtlessly the second half, with a captivating rendition of selections from Prokofiev’s celebrated ballet Romeo and Juliet.

Alsop made her debut with the Seattle Symphony back in 2005, a performance I recall fondly for a vibrant rendition of Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony. Back then, after earning notoriety in the conducting world at Tanglewood and leading orchestras in Eugene and Denver, Alsop was just entering the public eye. Alsop was establishing herself as a leading interpreter of the music of Barber, Bernstein, and other American composers. And the performance came just a few months before she became the first conductor to receive a “genius grant” from the MacArthur Foundation. Several years later she would take the podium as music director of the Baltimore Symphony, joining JoAnn Falletta as one of a few women to lead a major American orchestra. And her reputation since then has rightly soared. But back then, it was her expert knowledge and swaying presence that seemed to delight the audience and orchestra alike, and what I looked forward to with her return.

Continue reading Seattle Symphony’s season penultimate program celebrates Shakespeare’s Romeo and JulietA Grand and Intimate La traviata at Seattle Opera

Review originally published at Seen and Heard International

Verdi’s La traviata is one of the handful of operas that is instantly recognizable by the wider public. Since its premiere in 1853, it has never left the repertoire. Its legendary arias, such as “Sempre libra,” and its tragically realistic portrayal of a doomed love story captivate audiences to this day. From Maria Callas onward, every great soprano has tried to master the complex character of Violetta. Yet La traviata’s rich history and traditions pose a challenge to opera companies: how can you make this classic opera fresh and engaging for an audience that knows it by heart, even if they have never seen it live?

Fortunately for Pacific Northwest opera-goers, the Seattle Opera has risen to the challenge. Its current production of La traviata creates a grand experience by focusing on the work’s most intimate moments. The three main characters — Violetta, Alfredo and Germont — live in a world of decadence, privilege, and hierarchy, where lavish parties and balls contrast with country estates. The production’s sets reach from floor to ceiling, giving an imposing sense of scale. Though the sets at first glance might give the impression that this is a more traditional production, sharp lines and clean margins give it a modern touch and introduces an uneasy sense of isolation. Seattle Opera’s blithe chorus and crisp playing from the orchestra underscore the social atmosphere and the drama of the story. The lively atmosphere they create, makes it seem possible that anyone, especially Violetta and Alfredo, could ignore their troubles in the name of love.

Continue reading A Grand and Intimate La traviata at Seattle OperaRobertson and Geller impressive in Rachmaninov and Bartok

Sergei Rachmaninov was one of the most gifted and versatile composers of his generation. His music spanned a wide range of genres and forms, from piano pieces and songs to operas and orchestral works. His mastery of melody, harmony, and structure allowed him to create works that appealed to both the public and critics. But one night changed everything. His First Symphony, a daring and innovative work, was met with scorn at its premiere.

Rachmaninov had poured months of labor and love into this piece, and was left devastated and broken by the harsh judgment of his peers and mentors. His once-brilliant creative spark was smothered by a deep abyss of depression and self-doubt, which held him captive for three long years. Although he eventually recovered, the symphony almost vanished into obscurity, forever haunting the memory of its brilliant yet troubled composer.

Continue reading Robertson and Geller impressive in Rachmaninov and BartokTianyi Lu leads the Seattle Symphony in shapely performances of Strauss’ Aus Italien and Mendelssohn’s E Minor Violin Concerto

At just twenty-two years old, Richard Strauss made a bold decision to shift his compositional focus away from traditional forms such as symphonies. At around the same time, heeding the advice of Johannes Brahms, Strauss traded in his cold North European surroundings for the temperate climate and impetuous lifestyle of Italy, where inspiration struck. It was there that Strauss composed his early work Aus Italien, which broke away from the two conservative symphonies he had produced to date. Each of the piece’s movements is programmatic, foreshadowing many of Strauss’ future works, including his first “hit” Don Juan. However, Aus Italien still adheres to a traditional, symphonic structure with four movements, with the tone and temper of the German symphony.

Continue reading Tianyi Lu leads the Seattle Symphony in shapely performances of Strauss’ Aus Italien and Mendelssohn’s E Minor Violin ConcertoJ’Nai Bridges and Yonghoon Lee lead a thrilling concert performance of Saint-Saëns’ Samson and Delilah at the Seattle Opera

This review was originally published at Seen and Heard International

The last time Camille Saint-Saëns’ opera Samson and Delilah was heard in Seattle in 1965, Lyndon Johnson was in the White House and Seattle was basking in the afterglow of hosting the World’s Fair two years prior, with its new Space Needle adding a distinctive touch to the cityscape. That 1965 run featured a husband-and-wife duo: James McCracken in the role of Samson and Sandra Warfield as the temptress Delilah, whose vindictive quest ultimately devastates Dagon’s temple. Their performance was for more than half a century the Seattle Opera’s sole production of this lurid work — that is until General Director Christina Scheppelmann revived Saint-Saëns’ biblical epic as a concert performance for the 2022–2023 season.

Continue reading J’Nai Bridges and Yonghoon Lee lead a thrilling concert performance of Saint-Saëns’ Samson and Delilah at the Seattle OperaClassical Period shines in program featuring Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven piano concerti performed by Jean-Efflam Bavouzet and the Seattle Symphony

Originally published at Seen and Heard International

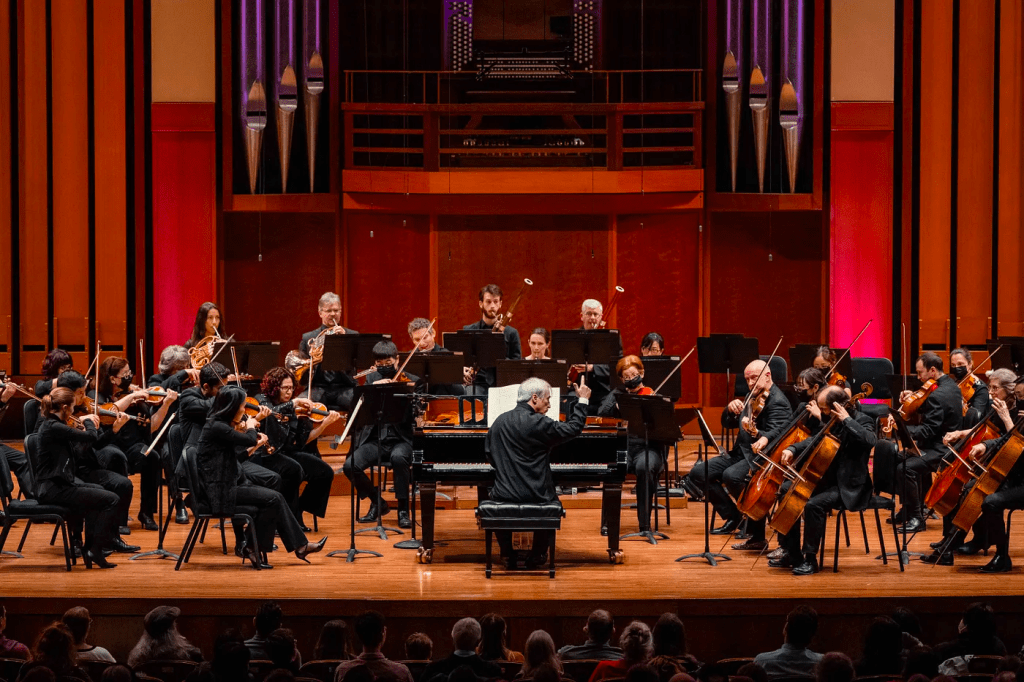

The names Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven are practically synonymous with Western music’s Classical Period. But while we may be familiar with the usual suspects in their repertoires, the Seattle Symphony’s recent concert program featuring pianist Jean-Efflam Bavouzet promised to be a refreshing take on these masters with a program featuring three of their lesser-known piano concerti.

Bavouzet and the orchestra opened the program with Franz Joseph Haydn’s Piano Concerto in F Major. Audiences don’t hear Haydn’s piano concerti as much as his pieces for violin and cello. Some of this may be a result of their ambiguous origins, but also the simple geniality of the writing which exudes courtly affability. But Bavouzet’s interpretation avoided these pitfalls, instead emphasizing the wit and energy of Haydn’s writing in a performance that felt like a true partnership with the orchestra.

Continue reading Classical Period shines in program featuring Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven piano concerti performed by Jean-Efflam Bavouzet and the Seattle SymphonyLitton and Kuusisto join forces to premier Enrico Chapela’s Antiphaser

Originally published at Seen and Heard International

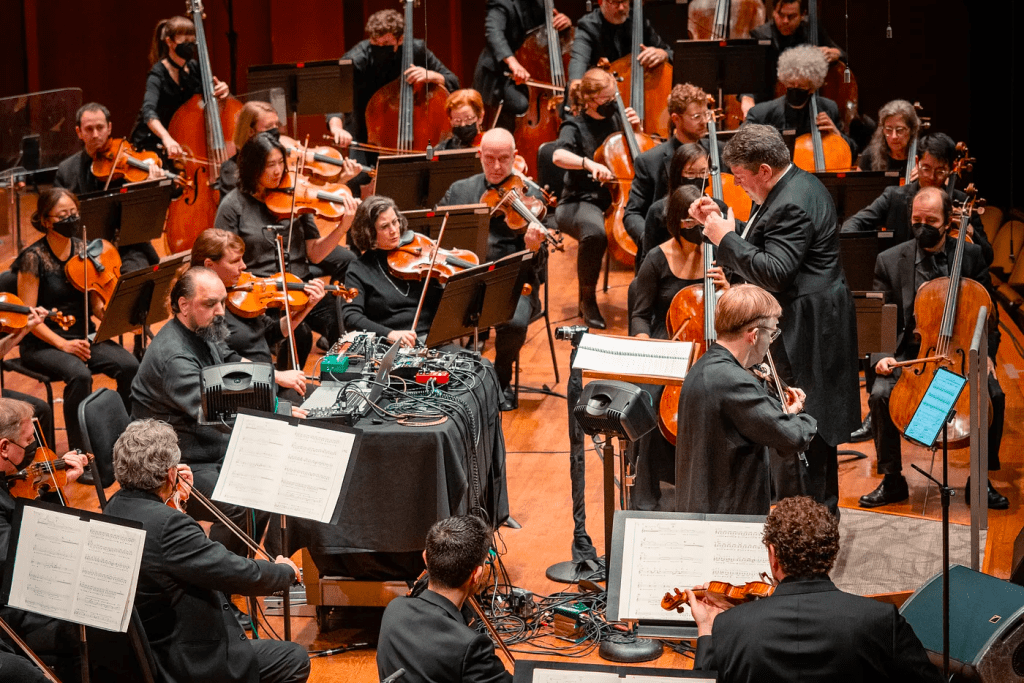

Concertos for electric violin are not common, but they are becoming more so. Established American composers — such as John Adams and Terry Riley — have written concertos for the instrument, but so too have newer voices like Brett Dean. After a world premiere performance this past weekend by the Seattle Symphony, we can add Mexican composer and guitarist Enrico Chapela to this exclusive but growing list. The orchestra and Finnish violinist Pekka Kuusisto, assisted by the composer, performed his new concerto for the instrument (Antiphaser) in Benaroya Hall. It had been co-commissioned by the Seattle Symphony which, even during its current artistic transition, has kept up an aggressive program of commissioning and performing new works.

Chapela describes Antiphaser as a cosmic thought experiment: what would someone see from the moon during an eclipse? His own eclectic musical background guides him in this endeavor to describe that which no one has witnessed. The son of a chemist and a physicist, he thought he would be a scientist as well, until he discovered the electric guitar, and music’s pull ultimately won out. Chapela pays homage to the scientific lineage in his family with compositions like Antiphaser and MAGNETAR (an earlier concerto for electric cello). But his style also draws in popular rock and metal influences with homage to the ‘masters’ whose works also expanded what was to be expected by orchestras and performers.

Continue reading Litton and Kuusisto join forces to premier Enrico Chapela’s Antiphaser