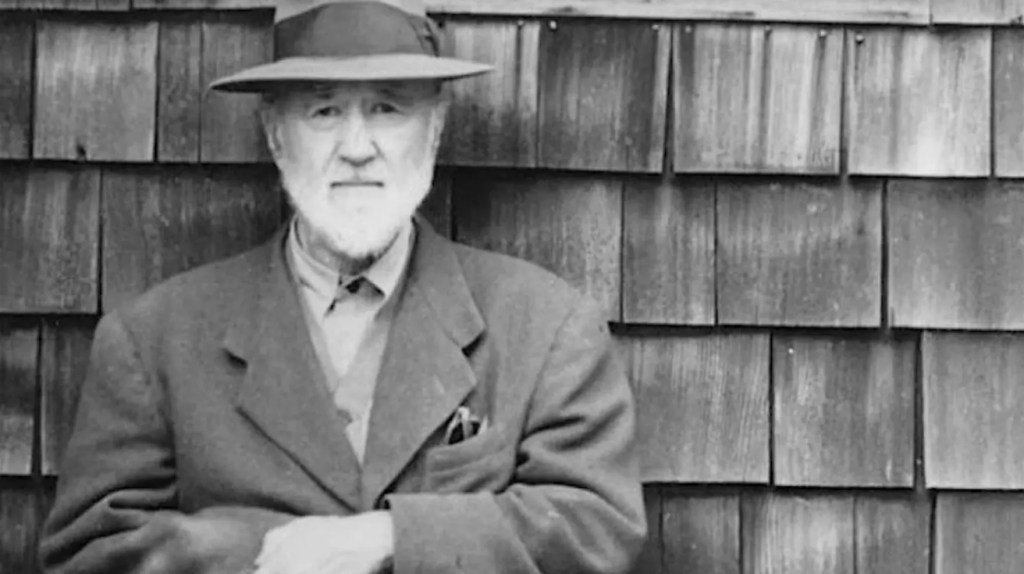

Charles Ives, one of America’s most adventurous composers, pushed the boundaries of classical music with his polytonal chaos, dissonances and American echoes. Yet, despite these innovations, he remains underappreciated compared to figures like Aaron Copland. In celebration of Ives’ 150th birthday last year, historian Joseph Horowitz is leading a campaign to elevate his legacy. Through blog posts, a documentary film, a radio program, and curated festivals, Horowitz is championing Ives’ music near and far. For Chicago audiences, the effort culminates in a special concert at the University of Chicago this weekend.

Despite Horowitz’s efforts to highlight Ives’ brilliance, his music remains challenging for many listeners. I discovered this firsthand last year when I immersed myself in his works for the anniversary. The experience of hearing so much Ives over a short period of time was often disorienting. Our ears have been conditioned by the European musical canon; our understanding of what American music sounds like has been shaped by composers like Aaron Copland. His most popular compositions, such as Billy the Kid and Appalachian Spring have come to define American classical music. Copland’s harmonies and lighter orchestration conjures scenes of vast open spaces of the American plains or mountain west. This sense of openness in Copland’s music, however, is shaped by more than just American landscapes—it also reflects his time studying with Nadia Boulanger in Paris, where he absorbed elements of French impressionism. Hints of Debussy and Ravel can be heard in his music. To my ears, Copland sometimes sounds like repackaged French impressionism with an American accent.

While Copland’s music embodies a European-influenced style, Ives takes a different approach—one rooted in the overlapping sounds of American life. Unlike Copland, who refined his craft through formal study in Paris, Ives was largely self-taught, absorbing music in a more intuitive, unconventional way. He grew up surrounded by the competing sounds of various bands playing in town squares and church hymns drifting through open windows, a chaotic yet deeply musical environment that shaped his ear. His father, a Civil War bandleader, encouraged him to experiment with music. As a result, Ives’ intricate layering of melodies doesn’t stem from academic intellectualism but rather from lived experience, memory, and a willingness to embrace the musical juxtapositions found in everyday life.

Ives fascinates me even more for this: he reveals himself as a fundamentally romantic composer steeped in American tradition. This idea dawned on me during a debate with a friend about his music. I fumbled through a defense of Ives, while my friend dismissed it as ‘exhausting noise.’ We went back and forth, unresolved. But reflecting on it later, I realized Ives embodies a kind of romanticism. Not the Brahms or Schumann variety, but a distinctly American one. His works often draw from transcendentalist philosophy, an American offshoot of European romanticism. With his deep emotional ties to place and memory, plus his love for programmatic elements, Ives aligns with romantic sensibilities.

Whether one finds Ives exhilarating or overwhelming, his music remains a defining piece of the American classical tradition. The upcoming Chicago Sinfonietta concert on February 22nd provides a perfect opportunity to explore some of the composer’s best works. The evening starts At 6 pm with baritone Sidney Outlaw and pianist Stephen Mayer giving a short recital of Ives songs. The orchestral program kicks off at 7 pm with George Walker’s Folksongs for Orchestra. This is a work in line with the Ives idiom – at times it is frustratingly abrasive, but elsewhere it harnesses musical nostalgia for great effect.

Ives’ Three Places in New England and Symphony No. 2 fill out the rest of the program. Three Places is undeniably a masterpiece. Across the work’s 20 minutes or so, Ives blends his own personal memories of each place, complex, layered textures, and quotations of familiar tunes. In the second movement, “Putnam’s Camp,” Ives recreates the frantic sound of a Fourth of July celebration by layering patriotic marches, folk tunes, and dissonant textures. This overlapping of familiar melodies mirrors the real-life experience of hearing multiple bands playing simultaneously, blurring the line between order and chaos. The piece ends with “The Housatonic at Stockbridge” – one of Ives’ most effective creations. The movement stands out for its serene, impressionistic quality, contrasting with the more tumultuous earlier movements. Ives paints the river’s gentle current with flowing string textures that ripple and overlap, suggesting the water’s movement and the haze of mist as it builds toward climax.

Ives’ Symphony No. 2 is a striking blend of tradition and innovation. Composed in his twenties, the piece remained unheard until 1951, when Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic finally brought it to life. While it may sound less radical to modern ears, at the time, it marked a departure from his more conventional Symphony No. 1. For the Symphony No. 2, Ives weaves fragments of Americana into a familiar four movement symphonic form with remarkable subtlety. The result is a seamless blending of ephemera which culminates in a climactic final moment that is unmistakably Ives.

Reflecting on that debate with my friend, I realize now that Ives’ music isn’t meant to be easily digested— it challenges expectations but rewards those who wrestle with what they are hearing. As the Chicago Sinfonietta presents his work this weekend, perhaps more listeners will come away with a deeper appreciation for Ives’ radical, profoundly American vision.

Tickets are still available, including pay what you can.

Discography

- Walker, Folksongs for Orchestra – There are very few recordings out there, but the Seattle Symphony’s recording conducted by Asher Fisch is probably the best.

- Ives, Three Places in New England – Eugene Ormandy and Philadelphia are masterful in this piece. There are a couple of different recordings out there, any of them will do.

- Ives, Symphony No. 2 – Bernstein’s later recording with the NY Phil is my favorite.

Discover more from Gathering Note

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.